Following several years of uncharacteristically large and severe wildfires, the Sierra Nevada region is in uncharted territory. In 2021 alone, approximately 1.5 million acres burned. Over half of those acres experienced high-severity fire, which kills at least 75% of vegetation. These fires have left behind an altered landscape that now includes vast expanses of dead trees. The change threatens our water supply, wildlife habitat, carbon stores, Native American sacred sites and biocultural values, and recreation opportunities.

Several Sierra Nevada communities are hurting deeply, with homes destroyed, livelihoods disrupted, and traditional ways of life further threatened. And some of California’s most precious natural resources—including crucial water sources like the Feather River watershed and beloved symbols like the giant sequoia—have been harmed.

We are not powerless in the face of these challenges. With action, we can help restore the resilience of our landscapes and protect the myriad values they offer, while also investing in community recovery and a restoration-based economy. Without action, however, dead trees may serve as fuel for the next fire.

While the task may feel daunting, recovery does not require novel actions and new strategies. Instead, recommitting to existing, proven strategies—while also developing a robust forest restoration workforce—can increase the resilience of our living forests, reduce the risk of reburning in areas that already experienced fire, and support the communities and industries that shape our region’s character.

Informed by our strong relationships with community partners, Sierra Nevada Conservancy has identified five strategies that respond to the region’s recovery needs while also building resilience for the future.

1. Landscape-scale forest restoration

After initial hazard-mitigation activities, protecting existing areas of live forest in, and adjacent to, burn areas should be a top priority. Land managers can safeguard these areas by capitalizing on the zones that experienced good fire, or fire that benefitted the landscape. In these places, which are now interspersed among the swaths of mostly dead trees, wildfire did the work of restoration by removing excess fuels and returning forests to a healthier, more resilient condition. To make the most of this silver lining, land managers can use prescribed fire to cost-effectively maintain areas of live forest. Strategic fuels reductions in high-severity burn areas will also be necessary to reduce the risk of reburning and to protect our remaining live forests from future high-severity fire.

At the same time, continued investment in landscape-level restoration treatments in unburned forests can build resilience to future fires. Pre-fire restoration is much more cost-effective than paying for fire suppression, post-fire hazard mitigation, and restoration of severely burned areas. Because key partners, such as the U.S. Forest Service, have limited resources to simultaneously engage in post-fire recovery and pre-fire restoration, we can use tools such as the Shared Stewardship Agreement and the Good Neighbor Authority to ensure we don’t have to choose between these two vital actions to protect our forests.

2. Water supply protection

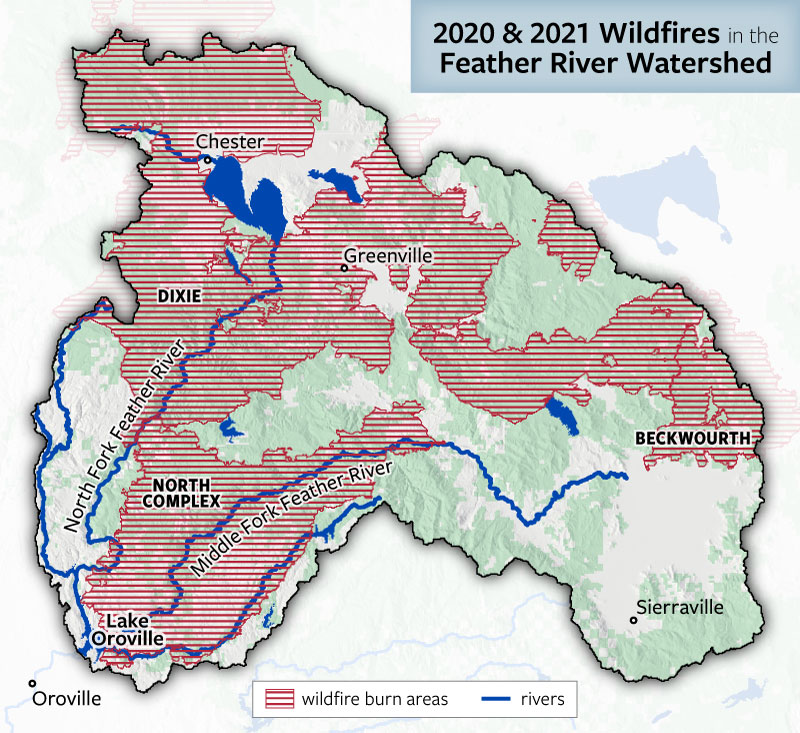

In 2020 and 2021 alone, approximately 55% of the Feather River watershed burned. Around 28% of the watershed experienced high-severity fire, meaning that at least 75% of above-ground vegetation was killed by fire. This vital water source now faces the risk of increased runoff and erosion, which can impact water quality, hydropower infrastructure, and reservoir capacity. The absence of vegetation can also expose the snowpack to direct sunlight and shift melt times to earlier in the spring. This shift creates challenges for communities, farmers, and ecosystems that rely on water stored in snowpack and reservoirs through the dry summer and early fall.

To protect the integrity of the Feather River and other source watersheds—which are recognized as critical components of the state’s water infrastructure in Water Code section 108.5—we can use science-based strategies to restore watershed productivity and resiliency. Actions, such as ecological thinning and prescribed fire to maximize snowpack retention, meadow and stream channel restoration, and voluntary private land conservation and management, could enhance the resilience of our water supply to fire and climate change. These same actions often simultaneously promote other forest values, such as habitat and stable carbon storage.

3. Strategic reforestation

In large high-severity burn patches, natural forest regeneration is less likely because there are few or no live trees nearby to provide seeds, seed banks in the soil are often damaged, and the trees that do sprout struggle to compete with fast-growing brush. Without our help, many severely burned forests may be replaced by chaparral for decades, if not generations. However, historical approaches to paying for replanting on federal lands—through the sale of burned timber, also known as a salvage sale—may not be sufficient. With a limited number of sawmills and a glut of burned trees, the supply of salvage logs now far exceeds demand, which severely curtails standard reforestation funding sources.

With a dedicated funding stream, we can give these forests a fighting chance to grow back and once again provide the services and values we depend on. Strategic, climate-smart replanting strategies—carried out in targeted areas and using diverse, native species and climate-resilience seedling varieties—can help ensure that forests grow back in locations that are especially important for carbon sequestration, water supply, recreation, habitat, and Native American practices. Funding for site preparation and ongoing post-planting management, including the early application of prescribed and cultural fire, also help trees successfully reestablish. Many of these techniques have already been successfully tested in the Sierra Nevada, including following the Camp and King fires.

Reforestation at scale will require a robust system of seed collection, seedling nurseries, and planting. A reforestation strategy developed by the Reforestation Working Group of the Governor’s Wildfire and Forest Resilience Task Force will lay out a path forward to ensure that the Sierra Nevada retains live, healthy forests into the future.

4. Rapid expansion of wood-utilization infrastructure

While not all burned trees can or should be harvested, post-fire salvage can be an appropriate strategy in certain areas to remove hazards and to allow for strategic reforestation. These trees can be used to make lumber, other value-added wood products, or fuel to produce clean, renewable energy—but only for a short time before the wood decomposes.

Typically, private industrial timber companies process a mixture of logs harvested from land they own and from nearby national forests. However, the current supply of standing dead trees exceeds what existing processing capacity can handle, so timber companies are focused on harvesting and processing trees on their own lands. As a result, independent logging companies have nowhere to sell logs they would normally harvest from national forests, which creates obstacles for salvage logging and cuts off revenue that historically funded reforestation on public land.

Burned trees can be harvested as sawlogs for only about 18 months after a fire. After five years, the wood falls apart and cannot be removed for any useful purpose. Without processing facilities, piles of dead, burned trees will sit and decompose, be pile burned, or serve as fuel for a future fire—releasing significant amounts of carbon.

A rapid expansion of wood-utilization infrastructure can help process dead trees and offset the long-term costs of forest restoration. Facilities can be developed at the scale and in the location that best supports both current recovery needs and ecological forest restoration. Funding for technical assistance, feasibility studies, preliminary designs, and equipment and property purchase can help communities and businesses leverage existing state programs, such as the Climate Catalyst Fund. The state can also help coordinate among federal and private partners to secure permanent financing and long-term stewardship contracts that create stability for potential investors in wood utilization infrastructure.

5. Support for community-led initiatives

Many Sierra Nevada communities have been rocked by recent wildfires, and some have experienced heartbreaking devastation. While state and federal disaster-relief programs often provide immediate support, other needs are more specific or take longer to reveal themselves. In these circumstances, the best strategy is often to listen to community members, who in many cases have a history of organizing themselves to collectively identify the best path forward. High-impact investments in community-led initiatives can significantly increase the welfare of fire-impacted communities.

The Sierra Nevada Conservancy recently employed this approach to support Indian Valley after its harrowing summer surrounded by the Dixie Fire. With nearly every hillside burned, residents displaced, and ranching and logging livelihoods disrupted, the community needed a way to process hazard trees, to create new opportunity, and—according to Jonathan Kusel, Executive Director of the Taylorsville-based Sierra Institute—to build hope. In response to the Sierra Institute’s request, SNC was able to modify a recent grant to enable the community-based organization to buy a small sawmill. This modest, but timely, investment is expected to aid recovery in Indian Valley and has the potential to “change the dynamics of Dixie Fire restoration and forest management across Plumas County.”

Other communities may have different priorities. Many tribes and Indigenous communities in the Sierra Nevada have suffered losses of culturally important sites and species, including pinyon pine and giant sequoia. Recovery investments can support their efforts to protect and restore fire-impacted sacred sites and biocultural values. Other communities hope to engage in post-fire planning, create a fire resilience buffer around the town, or increase their capacity to undertake recovery activities on top of their existing work.

The first step toward recovery

While full recovery for Sierra Nevada landscapes and communities will take time, the first step is clear. A rapid response can help protect all the Sierra Nevada region offers—stunning forested landscapes, precious water, natural habitat, sacred sites, abundant recreation, and more. At the same time, it is more important than ever to restore resilience to the green forests that we still have.

To meet the moment, we will need dedicated funds for these strategic actions and a robust workforce to undertake this work. With these pieces in place, we can make the meaningful and durable investments that our forests and communities are counting on.

For a deep dive into wildfire recovery in the Sierra Nevada, join SNC’s annual Watershed Improvement Program Summit on March 2, 2022. Community leaders, scientists, and land and water managers from across the region will share their perspectives on the importance of recovery in the Sierra, recovery work already underway, and what is needed to ensure success.