A letter from our Executive Officer

In 2021, the Sierra Nevada was the epicenter of the California wildfire crisis.

Unnaturally thick forests created by more than a century of fire exclusion were primed for ignition by a multi-year drought and record temperatures, hallmarks of climate change. The fires that started grew explosively.

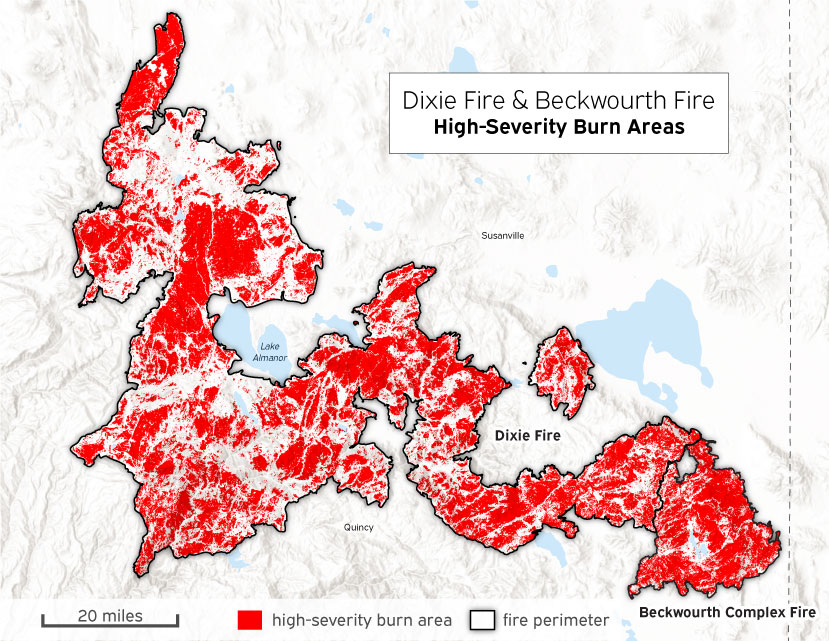

The result was another record-breaking fire season in the Sierra Nevada that, unbelievably, broke the record set just the year before. Two fires, including the Dixie Fire, which is the largest single-source fire in California’s history, burned up and over the crest of the Sierra Nevada. This has never happened before in known history, and they weren’t the only significant fires in the Sierra Nevada this year.

Tens of thousands of people evacuated their homes, including 40% of Plumas County residents. Many had to stay away for weeks, or longer. The historic towns of Greenville and Canyondam were damaged or destroyed. Smoke pollution from Sierra fires was so extreme, the air was dangerous to breathe over large parts of the state for weeks at a time. California’s national forests closed again, shutting down public access at a time when COVID 19 was driving record visitation to outdoor spaces across the state.

The Dixie and Caldor fires burned so intensely they left behind large landscapes, each bigger than San Francisco, in which all, or nearly all, vegetation was killed. In the Southern Sierra, high-severity fire killed groves of ancient giant sequoia trees that had weathered hundreds of lesser fires. The amount of high-severity fire far exceeded anything in our history books, or our understanding of what came before.

When the smoke cleared, it revealed stories of resilience that give me great hope.

In the Caldor Fire, where communities had received the support needed to create strategic fire breaks and defensible space, like the Fire Adapted 50 projects near Sly Park, firefighters were able to protect them. Where beneficial fire was reintroduced, like the Caples Creek Watershed Ecological Restoration Project, a megafire was unable to cause damage. Both are excellent examples of the kinds of solutions that SNC embraces.

More large-landscape restoration projects are either underway, like the French Meadows Project, or nearing completion of planning phases, like the North Yuba Forest Partnership and the Social and Ecological Resilience Across the Landscape (SERAL) projects. The SNC is supporting efforts like these across the region we serve through our Sierra Nevada Watershed Improvement Program (WIP) and the Regional Forest and Fire Capacity Program (RFFCP). Where plans are not as fully formed, we are investing in the capacity of regional partners and collaboratives to create project pipelines and regional plans and see them through implementation.

We know what the path toward wildfire resilience looks like for our region.

Sierra Nevada residents showed their resolve to persevere through extremely challenging times this year. The Feather River Resource Conservation District, a key RFFCP implementing partner, mobilized staff to bolster the ranks of fire-suppression agencies during the Dixie Fire, and trained others to join, as well. The SNC repurposed a portion of a grant to the Sierra Institute for Community and the Environment empowering the organization to partner with a local logging company to set up a small sawmill in Indian Valley. The mill will provide a much-needed market for hazard trees killed by the Dixie Fire and help the nearby town of Greenville recover and rebuild.

State and national leaders are making generational investments in the Sierra Nevada.

California committed $1.5 billion to forest and wildfire resilience in 2021 in an all-hands-on-deck effort to address California’s wildfire crisis. This included more resources than at any other time in the Sierra Nevada Conservancy’s history for us to support regional-wildfire-resilience efforts. It allowed us to award $19 million in wildfire and forest resilience grants to shovel-ready projects in 2021 and, as the new year begins, we are accepting proposals for an additional $25 million dollar grant round.

Governor Newsom’s 2022 budget proposes an additional $1.2 billion, including $100 million dollars for recovery efforts. An essential partner in this effort, the US Forest Service, is receiving significant resources that California’s national forests can put towards meeting commitments under a Shared Stewardship Agreement.

The intensity, and interconnectedness, of challenges facing California and the Sierra Nevada, make the Sierra Nevada Conservancy’s Watershed Improvement Program (WIP) more important than ever.

Simply put, restoring the region’s resilience to fire and climate change is essential to protecting the California way of life.

This requires maintaining our focus on forest health and recognizing how goals across the landscape are deeply intertwined. Opportunities for all to experience the outdoors have inherent value, and build appreciation for these vital landscapes, while helping to sustain the local communities necessary to steward them. Natural and working lands, that might produce agricultural products, often provide important ecosystem services like carbon storage, wildlife habitat, or natural fire breaks. The WIP will support these opportunities, as well.

I’m proud of the work that the SNC has accomplished with our partners over the past year. I hope that the stories of partnership, landscape and community resilience, and perseverance in our 2021 Annual Report can serve as important reminders of what we can achieve together—and inspire us to continue striving towards our shared goals.