As California wraps up a third consecutive dry year, dead and dying trees are adding splotches of orange and brown to many landscapes in California’s mountains this year. The discoloration of familiar alpine forests is the result of tree mortality due to drought, insects, or disease (everything other than wildfire) that is tracked through annual aerial surveys conducted by the U.S Forest Service.

New tree mortality a reminder of the not-so-distant past

In 2022, preliminary results from the U.S. Forest Service’s Aerial Detection Survey, and field observations, suggest the emergence of a new tree mortality event disproportionately impacting higher-elevation fir forests in the northern and central parts of the state.

For some Californians, it has evoked a not-so-distant memory of the devastating southern Sierra tree mortality outbreak on the heels of the 2012–2016 drought, and the dangerous and unprecedented behavior of the 2020 Creek Fire that burned through the heavily impacted areas. For others, particularly in the central and northern part of our state that was largely unaffected by that event, it raises new concerns about forest ecosystem health and mounting wildfire risk.

What happens next will depend on future weather patterns, and whether land managers can catch up on long-needed forest-restoration efforts.

Drivers of tree mortality

Large-scale tree mortality is mainly driven by abnormally high temperatures and prolonged drought, as scarcity of water strains otherwise healthy trees. The lack of water supply is exacerbated by increased competition among trees located in dense forests.

Unfortunately, many forests throughout the Sierra Nevada are two to five times denser than historical levels, largely due to removal of fire from the landscape. The dense stands of weakened water-stressed trees are more susceptible to diseases and insect infestations.

High-elevation fir trees in northern and central California hit by emerging mortality event

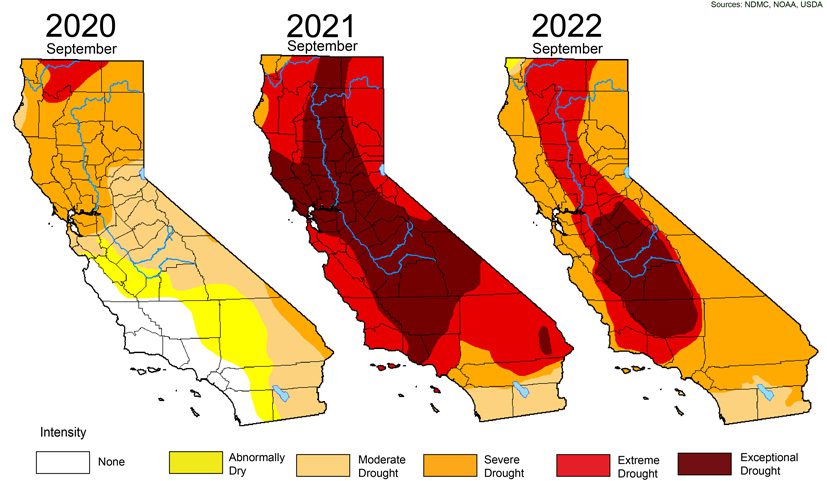

Drought conditions, high temperatures, and dense forests drive tree mortality throughout the Sierra Nevada. Following California’s third consecutive dry year, and record-low precipitation during the 2021 snowy season, tree mortality is showing up in places that were largely spared during the 2012–2016 tree mortality event centered in southern Sierra pine forests.

Jeffrey Moore, the USFS Region 5 Aerial Detection Survey Program Manager, stated: “Tree mortality has definitely shifted north. The key difference is during the first outbreak it was low-elevation ponderosa pine that went out first. This time around it is concentrated in fir, typically at higher elevations.”

Although preliminary, those results also suggest that the fir-mortality event could result in significant changes to alpine forests. For example, fir mortality in the Northeastern survey area, which covers the eastern part of the state from south of Lake Tahoe to California’s Oregon border, was “generally more intense, often at moderate to severe intensities.” Moderate to severe intensities mean 11–50% of individual trees surveyed in that area had died in the past year and translate to noticeable and significant changes on the landscape.

Environmental, social, and economic impacts of declining forest health

The Sierra Nevada Conservancy’s State of the Sierra Nevada’s Forests Report, published in the aftermath of the 2012–2016 tree mortality event that transformed many southern Sierra forests, makes clear the high stakes of the forest-health crisis. That report outlined the direct environmental, social, and economic impacts of widespread tree mortality in Sierra Nevada forests, such as increased fire danger as more dead, dry fuel accumulates after a widespread mortality event.

Recent record-setting fire seasons underlined the impact tree mortality can have on wildfire behavior as research suggests that the explosive growth of the 2020 Creek Fire was driven by mass fire behavior made possible by the high amount of dead biomass alongside overly-dense live trees within the fire’s interior.

Other significant impacts include:

- Loss of a significant amount of carbon absorbed and stored, and an increase in greenhouse gas emissions. In 2021, more than 7 million trees died throughout the Sierra—many of them large trees that were absorbing and storing large amounts of carbon. Those trees are no longer actively sequestering carbon, with nothing to replace that loss over the short- to medium-term.

- Loss of critical wildlife habitat. Sierra forests are home to 60 percent of California’s animal species. Over one-third of them are listed by the Department of Fish and Wildlife as rare, threatened, or endangered, but current forest conditions make the protection of their habitat extremely challenging.

- Threats to public safety and infrastructure from falling trees. Prevalent dead trees present safety risks by increasing the likelihood of falling trees to Californians living in rural, forested communities, inhibit emergency response and evacuations if falling onto roads, and damage critical infrastructure such as powerlines.

- Financial burden on local homeowners and local/state government to remove dead trees.

- Loss of revenue from tourism and recreation as facilities are closed or limited due to public safety risks from falling trees.

Proactively treating forests can increase resilience to climate change

California’s last tree mortality event decimated southern Sierra landscapes and set the stage for historically destructive wildfires, like the Creek Fire. Although the course of the emerging tree-mortality event is not yet known, the recurrence of severe drought underscores the urgency of restoring resilience to California’s Sierra Nevada and Cascade forests.

Management strategies, such as mechanical thinning, prescribed burns, and diversifying the age and species of stands decrease forest density and encourage biodiversity. Both result in a forest that is more resilient to drought, disease, and wildfire. These are steps we can take now to protect California landscapes under mounting pressure from wildfire and climate change.