The 2020 fire season highlighted just how destructive fire can be when climate impacts like drought and prolonged periods of extreme fire weather collide with unhealthy, overly dense forests. As Governor Newsom put it while surveying damage from the North Complex Fire at Oroville State Recreation Area in the Sierra Nevada foothills: “This is a climate damn emergency.”

He was right, and not just because of the damage on the ground. Sierra Nevada megafires aren’t merely a symptom of an emerging climate crisis, the greenhouse gases they release may make the problem worse.

Forests play an important role in regulating our climate. Trees absorb carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere and store it as carbon, offsetting emissions associated with burning fossil fuels. Wildfires are a natural occurrence, and emissions from wildfires are considered natural. At the same time, the wildfires we’re experiencing today are extremely out of character for the region, and the emissions associated are significantly out of balance with historical events.

Staggering greenhouse gas emissions

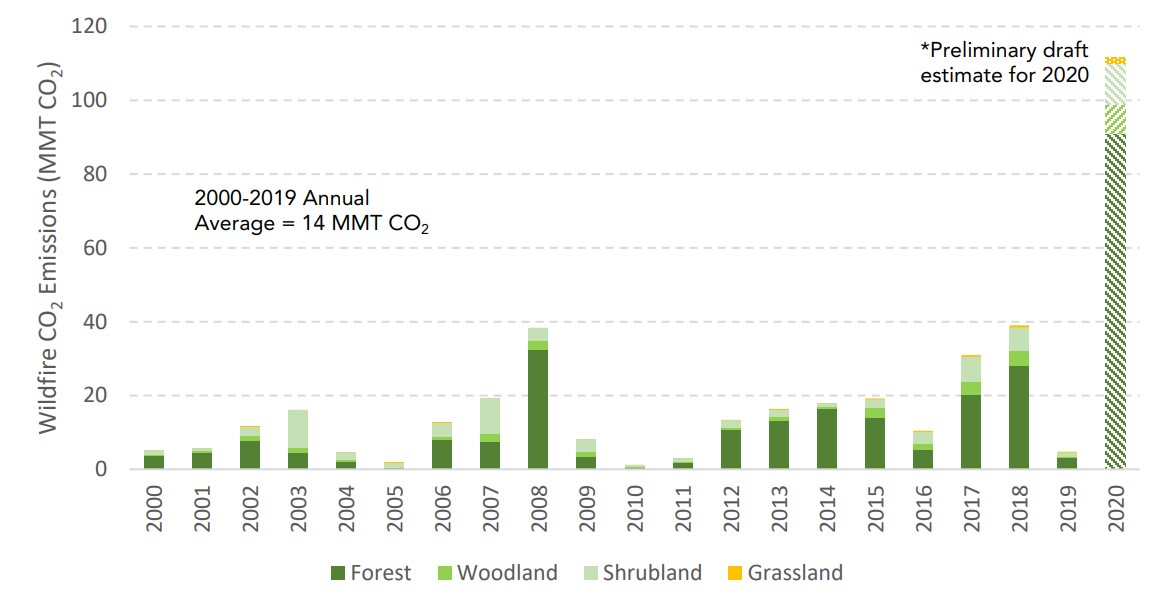

A December 2020 report by the California Air Resources Board (CARB) used a vegetation combustion model and geospatial fire perimeters to calculate annual wildfire CO2 emissions in California for the years 2000–2019 and provided a preliminary draft estimate for the 2020 wildfire season. They estimate that the 2020 fire season produced nearly 115 million metric tons of CO2, a staggering amount.

For context, if the 2020 figures prove accurate, wildfires created nearly triple the amount of CO2 than any other year on record, and according to California’s most recent Greenhouse Gas Emission Trends report, more climate pollution than either the industrial or power sectors of California’s economy produce in a year. Only annual transportation emissions eclipse the 2020 wildfire season as a source of greenhouse gases.

Resilient forests pollute less

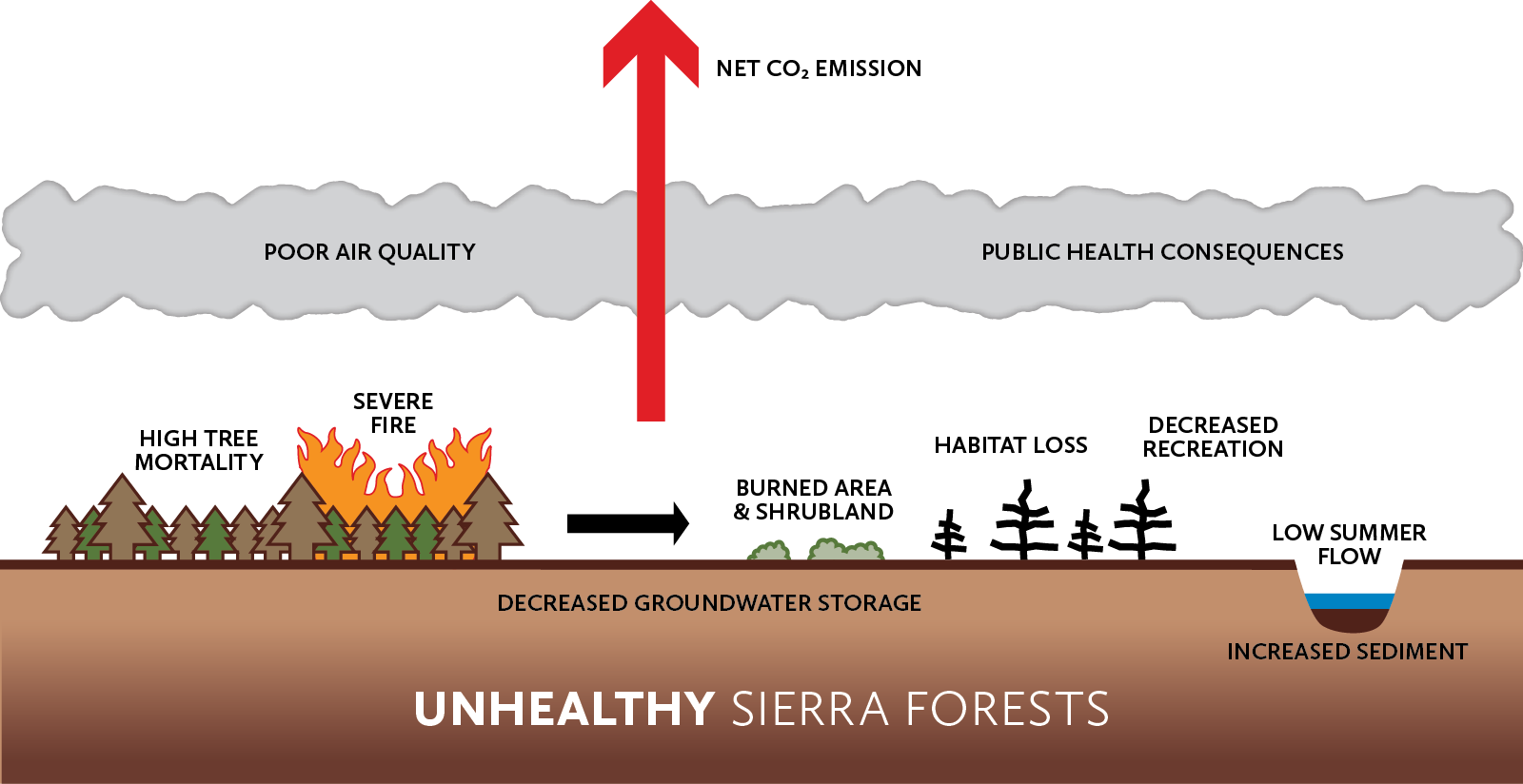

One reason for the dramatic increase is that the high-severity wildfires that are burning today create more emissions per acre than historic fires. CARB analysts have found that wildfire emissions averaged 7.5 metric tons of CO2 per acre in the past compared to 22 metric tons of CO2 per acre today.

Making matters worse scientific research suggests that Sierra Nevada forests that burn in large high-severity wildfires will remain net-emitters of carbon for decades after the event and points out the growing risk of permanent conversion from forest to shrub or grasslands, vegetation types that store 90% less carbon.

Wildfire emissions like 2020 are not inevitable—forest health work can stabilize our stocks of forest carbon in the face of climate change. Prescribed fire and ecological thinning are both effective tools that reduce the risk of catastrophic wildfire, and associated carbon emissions, by shifting live carbon stocks from thick stands of small-diameter trees that are vulnerable to fire to larger diameter trees arranged in forest structures that are more resilient to fire.

Emerging policy solutions

There are also encouraging signs that state and federal wildfire policies for the Sierra Nevada are catching up to the science.

In mid-2020, California and U.S. Forest Service signed a shared stewardship agreement formally committing to conduct ecological restoration on a combined one million acres per year in the state. In January 2021, California’s Wildfire and Forest Resilience Action Plan laid out a roadmap for addressing key barriers to achieving the state’s ambitious forest resilience goals. That plan was stakeholder-driven, bringing together nonprofit, industry, and governmental entities to identify approaches that are working and gaps in California’s existing wildfire and forest resilience strategy.

Mere days after the Wildfire and Forest Resilience Action Plan was released, the Governor’s budget proposed $1 billion in aligned funding. The legislature is currently weighing in on the administration’s plans and there is significant legislative energy going towards securing adequate resources to make a meaningful difference on the ground.

We’re hopeful that these conversations will result in significant investment across California, and the Sierra Nevada Watershed Improvement Program stands ready to support this much-needed work.