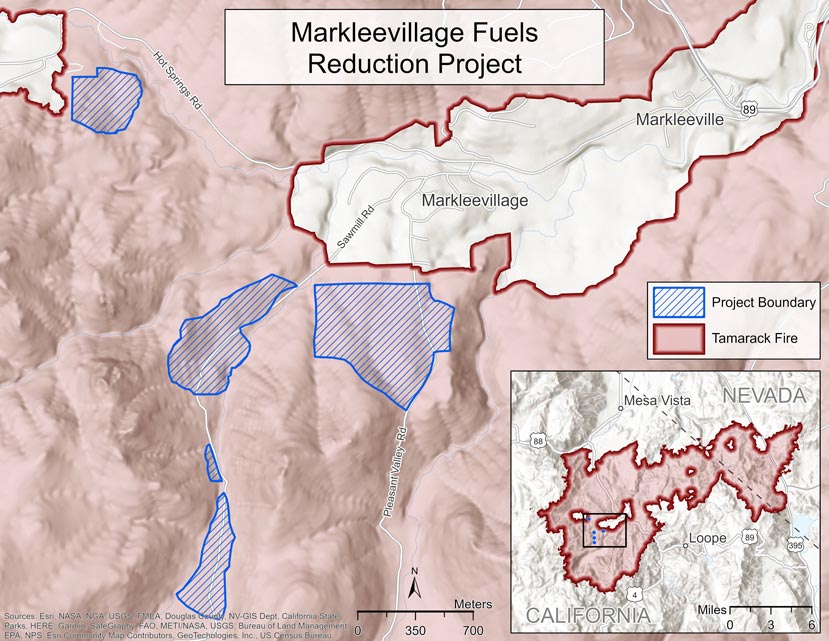

In the heat of the 2021 fire season, the Tamarack Fire burned toward the small, rural community of Markleeville in Alpine County. A year later, the town of Markleeville still stands flanked by ridges covered in a charred blanket of trees. It persists thanks to a network of fuel-reduction projects around the town, including the Markleevillage Fuels Reduction Project (Markleevillage Project) funded by the Sierra Nevada Conservancy (SNC), and the heroic work of firefighters.

The neighborhood of Markleevillage sits at the edge of town and the base of steep forested canyons of the Humboldt-Toiyabe National Forest. In between the two, lies the Markleevillage Project.

SNC-funded Markleevillage Fuels Reduction Project

Completed in 2019, the 234-acre project reduced hazardous fuels, seeking to provide multiple benefits to the local watershed by increasing forest vigor, enhancing local wildlife habitat, and improving water-filtration ability.

Most importantly, the Markleevillage Project was designed to protect the lives, homes, and infrastructure of the community in the event of a wildfire.

“The Sierra Nevada Conservancy grant that came four years ago to Alpine County really has helped the neighborhood it was used on. Those people in that neighborhood sleep much better because of that protection that was built in between the forest and their homes,” said Alpine County Supervisor Ron Hames in 2021, less than a year before the Tamarack Fire.

And, based on the survival of that neighborhood during the Tamarack Fire, that confidence was well-placed.

When the Tamarack Fire arrived at the edges of the Markleevillage Project, it changed from a blazing crown fire in the untreated forests to a less intense fire. This allowed firefighting crews to safely fight the blaze and protect the homes nearby.

Multiple-benefits mean multiple ways to succeed, and fall short

A multi-benefit nature-based solution like the Markleevillage Project can be successful even if many trees die when it is burned over during a wildfire.

Much of the landscape within Alpine County is steep, remote, and inaccessible wilderness. As a result, forest health and resilience work in the county is focused near communities. This makes sense both because that is where it is most cost-effective to get work done and because locating fuel-reduction efforts near homes can maximize life-and-property-saving benefits.

On this front, the Markleevillage Project was an unequivocal success.

Evaluating the ecological benefits to the forests in the Markleevillage Project area is far more difficult to pin down with any level of certainty. The severity (a term used by fire scientists to describe a fire’s effect on the landscape) with which a fire burns a particular area depends on many factors, like terrain and weather in addition to fuel availability. The forests treated by the project burned somewhat less severely than the Tamarack Fire as a whole, and have a stronger prognosis for recovery as a result.

Furthermore, even though Markleevillage Project forests fared somewhat better than untreated areas, surveying stands of burned dead trees in the project boundaries, it’s clear that many of the Markleevillage Project’s other benefits, ranging from increased forest vigor to habitat or water-filtration improvements were damaged by the Tamarack Fire.

Just as the unburnt homes stand as a testament to the project’s benefits, the burned landscape in which they sit is an important reminder that evaluating how a project performed, especially in the aftermath of a large damaging wildfire, is not always simple. Particularly for multi-benefit projects, the outcome is rarely a binary result of either success or failure.

And it’s also a reminder that we can, and must, do more to protect the forests of California’s Sierra Nevada and Cascade mountains.