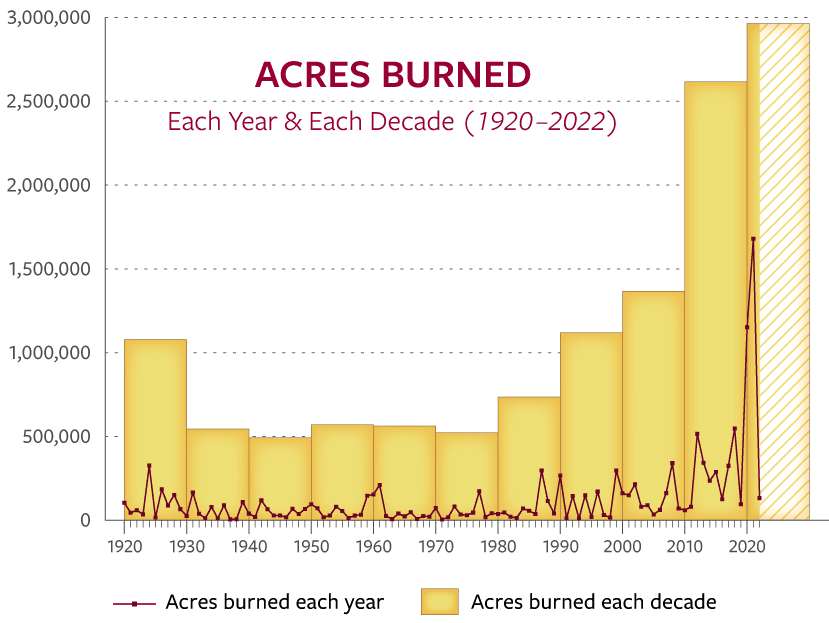

The 2022 Sierra Nevada-Cascade fire season was relatively quiet, with approximately 132,000 acres burned, compared with the record-breaking 2020 and 2021 fire seasons, which burned 1.1 million and 1.6 million acres in the Sierra, respectively.

The consensus among fire specialists and resource managers is that the mild 2022 fire season is not indicative of a change in a concerning trend towards larger and more destructive fires.

Concerning high-severity fire trends continue

Although fewer acres burned was a welcome change from the record-setting 2020 and 2021 fire years, acres burned is just part of the story—over 70 percent of the total acres is attributable to just two of the largest fires: the Mosquito and Oak, which burned at 30 and 60 percent high severity, respectively.

These large high-severity fires continue a disturbing trend in which modern fires are burning at higher proportions of high severity and in just a few large mega-fires. This contrasts with the historical fire regime that predated western settlement in which many more smaller fires burned with less severe effects across the landscape.

Especially worrisome are large patches of high-severity burn because these areas are less likely to see natural conifer regeneration and are particularly vulnerable to reburning at high severity, increasing the chances of conversion to non-forested conditions.

Active management can mitigate impacts of high-severity wildland fire

The Oak Fire in Mariposa County is an example of a damaging high-severity fire: nearly 60 percent of the almost 20,000-acre fire burned at high severity, destroying over 200 structures with untold impacts to local habitat and waterways.

There are, however, reasons for hope: where the Oak Fire burned onto an actively-managed ranch, including the footprint of the SNC-funded Clarks Valley Wildfire Reduction Project, fire effects left healthy green forest.

This project, completed in 2020, removed trees killed during the 2016–17 tree mortality epidemic. The Clarks Valley project was part of a watershed health project intended to help restore the Clarks Creek watershed and reduce the risk of high severity fire. The removal of fuels undoubtedly contributed to the lighter impact of the Oak Fire in that area. The success of this project underscores the multiple benefits of fuels reduction and biomass removal treatments.

The green lining: wildfires provide beneficial treatments too

There is, however, a silver (or in this case, green) lining, as well—while the sheer number of acres burned in the last five years is staggering, with far too much burning at high severity, hundreds of thousands of acres of Sierra-Cascade landscapes have also burned with a mixture of beneficial low and moderate severity fire effects. The 2022 Red and Rodgers fires, for example, which burned inside Yosemite National Park far away from homes and infrastructure, were managed with minimal suppression techniques, ultimately leading to over 11,000 acres of beneficial fire treatments.

Managers continue to explore ways to leverage these “good” burn areas to anchor future treatments or maintain beneficial effects. In fact, even the large and damaging 2021 Dixie Fire had some areas in which low- and moderate-severity fire had a net positive impact. Land managers working on the SNC-funded Bootsole project are using some lower-severity burn areas within the Dixie footprint to build resilience in the Plumas National Forest.

Elevated fire risk, with high-stakes for California, persists in the Sierra-Cascade

At the close of 2022, 91 percent of California was in a “severe drought,” and although recent atmospheric storms have helped alleviate concerns about another dry year, high levels of precipitation on recent high-severity fire scars have likely contributed to downstream flooding. The high-severity portion of the Caldor Fire may have been a significant factor in flooding Sacramento County in early 2023.

Evidence of the drought showed up in the 2022 aerial detection survey that noted a significant uptick in tree mortality, especially in red fir. This mortality will contribute substantial dead biomass to the landscape, increasing the chances that future wildfires will burn at higher severity, underscoring the relationship of cascading climate-influenced risks of drought, fire, and flood.

Making matters worse, recent research showed almost a third of Sierra Nevada forests south of Lake Tahoe converted to sparsely-treed landscapes or shrubland between 2011–2020, both of which store far less carbon than healthy forest ecosystems. Newly released modeling results show that the emissions from the 2020 wildfires essentially negated two decades of greenhouse gas emission-reduction work from other sectors in California, underscoring the importance of Sierra-Cascade stores of forest carbon to meeting state climate goals.

It all contributes to an emerging awareness of the interconnectedness of wildfire, flood, drought, and climate risks, and the important role that stewarding California’s Sierra-Cascade plays in creating a resilient California.