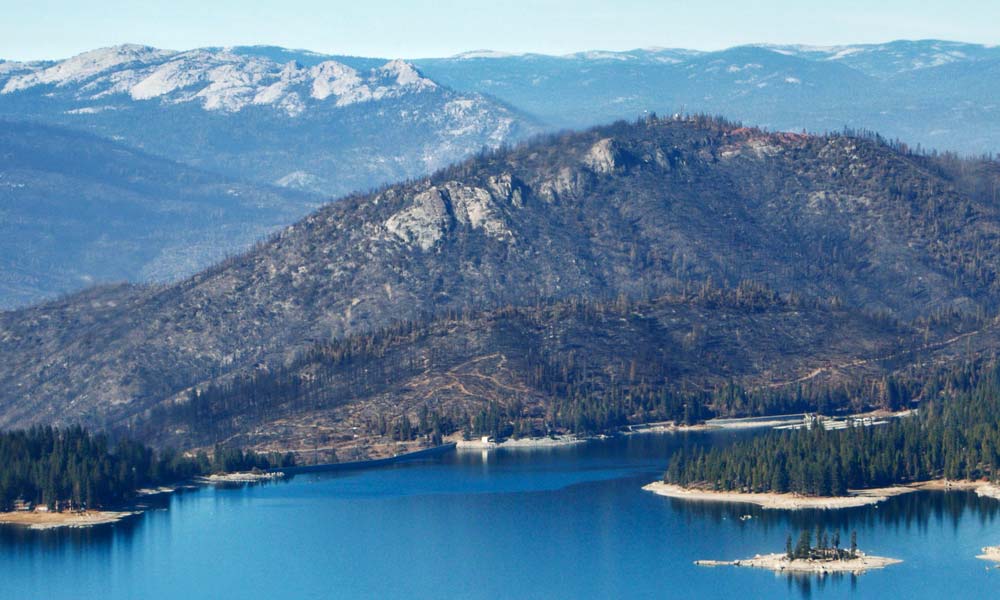

The forested watersheds of the Sierra Nevada are the origin of more than 60 percent of the state’s developed water supply. Sierra Nevada megafires that kill all, or nearly all, vegetation across large landscapes pose serious risks to this system.

In the immediate aftermath of a fire, high-severity burn areas lack vegetation to stabilize soils. Making matters worse, the intense heat can cause the soils themselves to change in ways that reduce their ability to absorb water during rain or snowmelt events. This means that high-severity burn areas can experience runoff and erosion rates five-to-ten-times greater than low- or moderate-severity burn areas. The resulting sediment enters nearby creeks and rivers, degrading water quality and adversely affecting regional aquatic habitats.

Plumes of sediment from post-fire rain events can also impact reservoir operations until the sediment settles out to the bottom. Once there, it reduces water storage capacity. Adapting to and cleaning up from these sedimentation events can be a difficult and expensive process for the owners of water infrastructure.

Three Sierra Nevada megafires create risks for California water supply

The 2020 North Complex, Creek, and SQF Complex megafires created high-severity burn areas of unprecedented size in three watersheds important for California’s water supply.

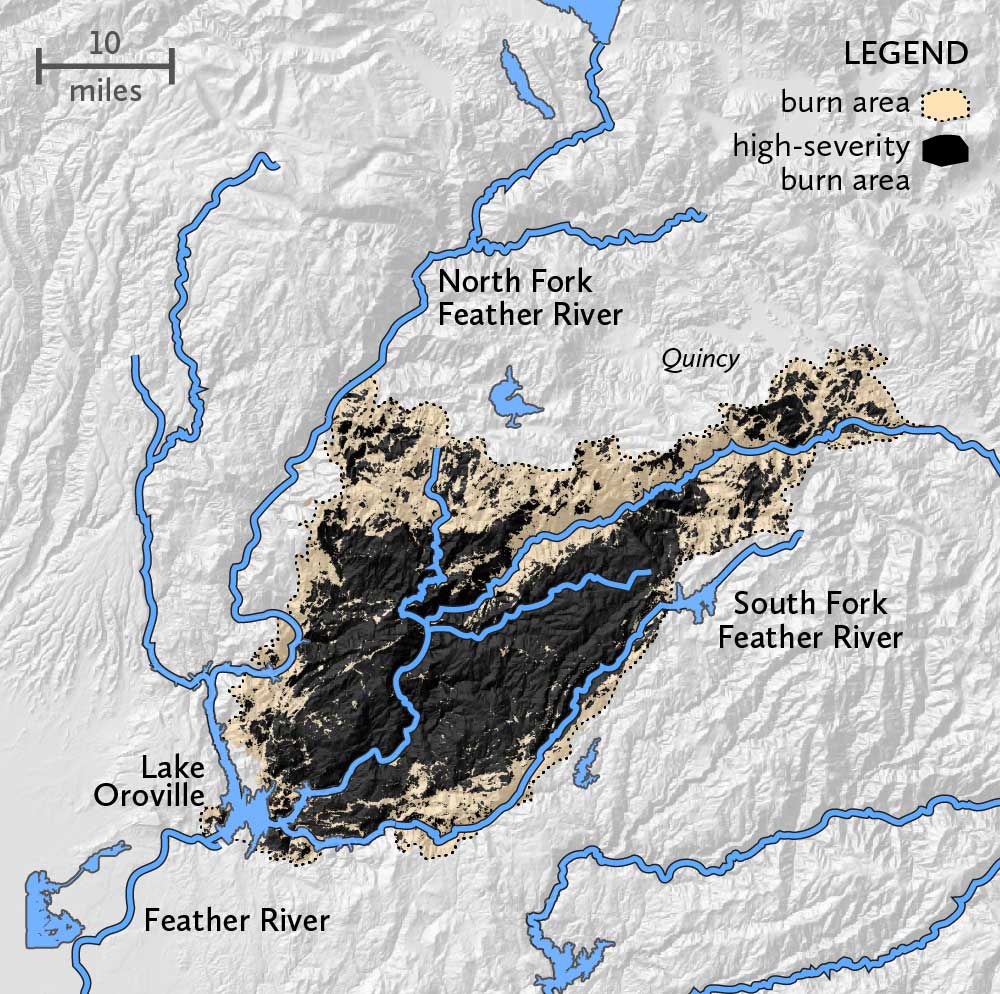

North Complex Fire and the Feather River

The North Complex Fire, the second largest in Sierra Nevada history, burned approximately 319,000 acres in the Feather River watershed. An astonishing 58 percent burned at high-severity. The Feather River is the source for the Oroville-Thermalito Complex consisting of Lake Oroville and a series of associated hydroelectric generating facilities. Lake Oroville is the second-largest reservoir in California and the largest source of water for the State Water Project. The State Water Project is the backbone of California’s water distribution system, providing water for home, farm, and industrial use in the San Francisco Bay area, the San Joaquin Valley and Southern California. The hydroelectric facilities have a combined capacity of more than 750 megawatts.

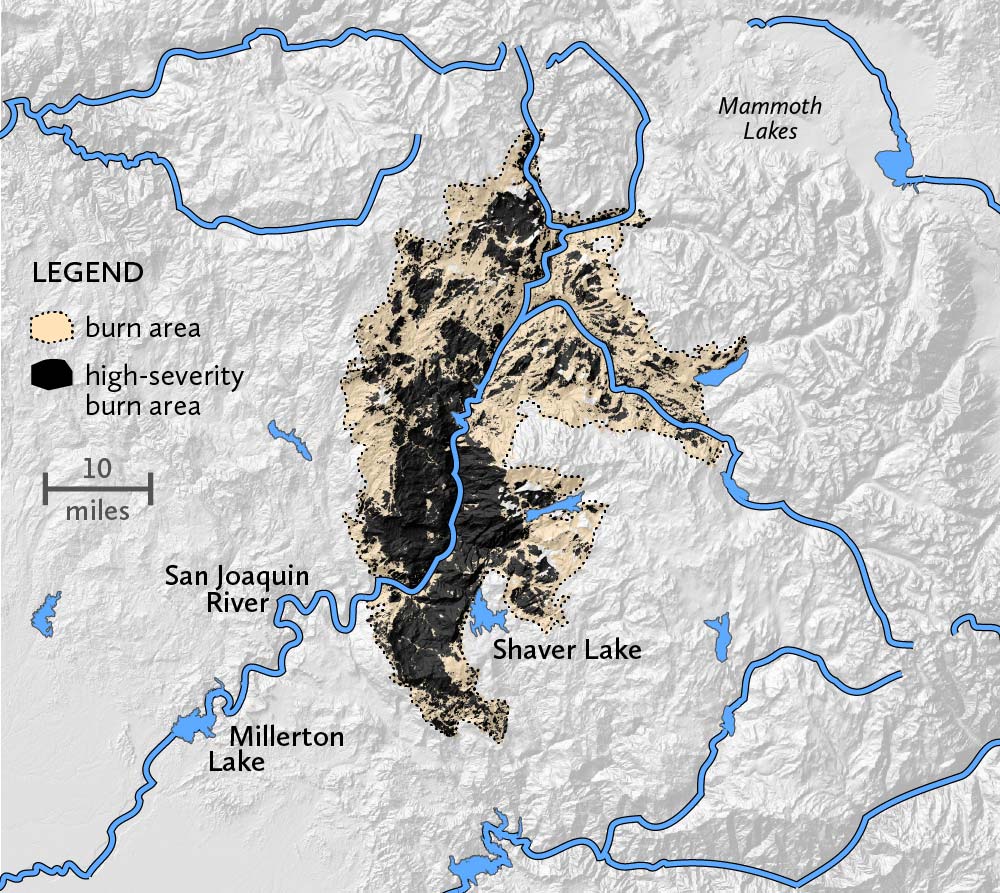

Creek Fire and the San Joaquin River

The Creek Fire is the largest in the history of the Sierra Nevada. It burned roughly 380,000 acres of the San Joaquin River watershed, 43 percent at high-severity. The San Joaquin River flows to Millerton Lake where it is impounded by the Friant Dam, the source for both the Madera and Friant-Kern canals. Water stored here supports a million acres of agricultural production throughout the fertile San Joaquin Valley.

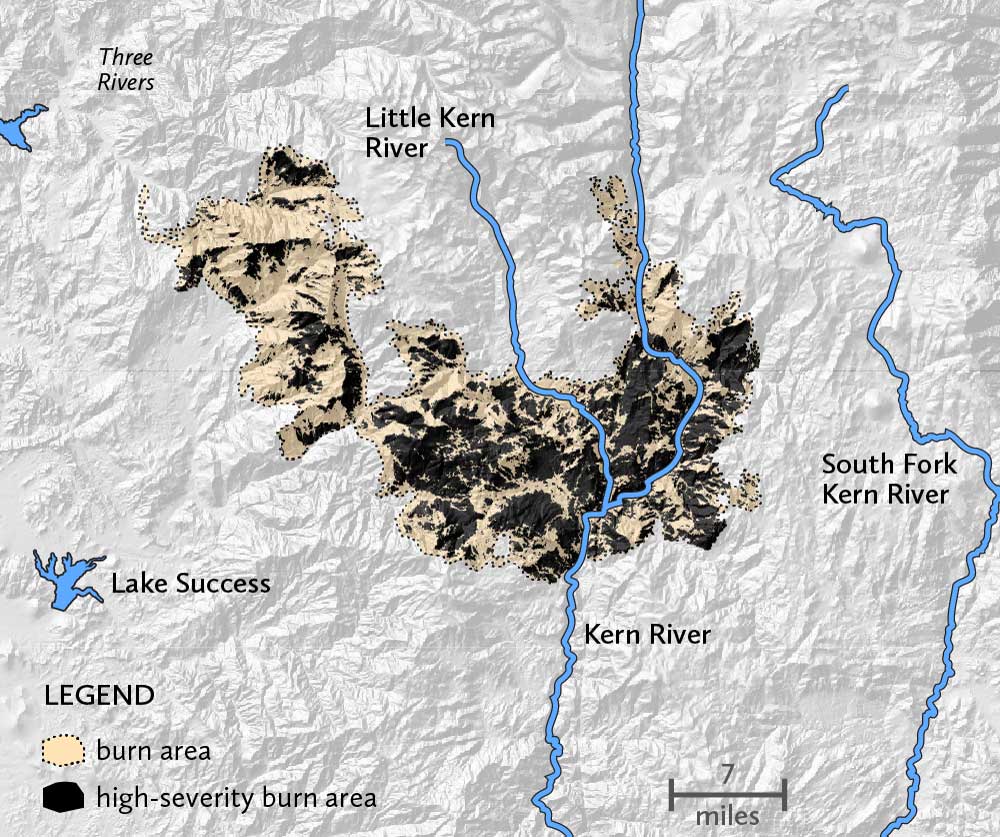

SQF Complex Fire and the Kern River

The SQF Complex Fire, is the fifth largest on record in the Sierra Nevada. It burned nearly 175,000 acres in the Kern River watershed, 43 percent at high-severity. The Kern River is the southernmost river in the Sierra Nevada and source for Lake Isabella, a reservoir roughly 40 miles Northeast of Bakersfield that holds water utilized for drinking, irrigation, and groundwater recharge in the Southern San Joaquin Valley.

The water costs of fire

We won’t know what challenges these 2020 megafires will create for downstream water systems for several years, and depending on the amount and timing of precipitation, the worst sedimentation impacts may not materialize. At the same time, Placer County Water Agency’s (PCWA’s) experience in the aftermath of the 2014 King Fire suggests that the water costs of the 2020 fire season may well prove significant.

Those expenditures, $5–10 million each time one of their reservoirs must be cleaned and up to $200,000 for each day a hydropower plant must sit idle, led PCWA to join the SNC, Tahoe National Forest, The Nature Conservancy, Placer County, American River Conservancy and UC Merced in the French Meadows Partnership. The collaborative’s successful French Meadows Restoration Project is proactively reducing fire risk through ecologically-sound fuel-reduction treatments across a 28,000-acre landscape and winning a 2020 Regional Forester’s Award in the process. Less than 100 miles to the north, the SNC is helping to fund the North Yuba Forest Partnership, another collaborative (that includes the Yuba Water Agency) that is planning work across an even larger 275,000-acre landscape. In both instances, multiple public entities are joining local and national nonprofit organizations and industry representatives to work towards common goals of more resilient forests and forest communities.

With assistance from Sierra Nevada Watershed Improvement Program grants, these forward-looking collaboratives are investing in resilience now to avoid paying for disasters later. Both Placer County’s King Fire experience and research conducted by the SNC, the Mokelumne Avoided Cost Analysis, suggest that this is a prudent financial decision for water agencies, land managers, timber interests, and governments alike.